Sustainability – a tale of two definitions

By Lucy Gatward, Better Food’s Marketing Manager and keen observer of Bristol’s food environment

(it’s quite long – you might want to pop the kettle on)

Definition 1: Food security – why does everyone keep telling me not to buy cheap food?

Definition 2: The environment – how can independent retailers help fight climate change?

What does the diet of the future look like?

Conclusion and sources

Nature is marvelous. It’s persistent, it’s intolerant, its ability to diversify into a gazillion directions of organised chaos is magnificent. Humans too are magnificent, yet when we mass together, our instinct is often to do the opposite – in a search for efficiency, we streamline, simplify and generalise. Nuance is messy …

Maybe in some way this explains how we’ve arrived at our current situation regarding food; from production to disposal, on its journey across the world into supermarkets, the food service industries, the en masse feeding of our school children and hospital patients. In short, the idea, particularly in the West, is that the world is our food basket, and the goal is to move it from one area to another as quickly, efficiently and cheaply as possible.

And this is how it’s worked, sort of, for the last 70 years.

Now it’s clear that things need to change, we’re beginning to think differently about how we use the world’s resources – in this case food – in order to live more sustainably. But this global matter needs a network of local solutions. Like nature, we need to diversify …

This is my Bristol-eye view …

Definition 1: Food security – why does everyone keep telling me not to buy cheap food?

Why is having a network of local food producers, shops, food services and customers important?

Why is having a network of local food producers, shops, food services and customers important?

Why can’t we just get it all cheap from the supermarket?

Back in 2011, Joy Carey (a Sustainable Food System Planning consultant) wrote a study called Who Feeds Bristol – Towards a resilient food plan, commissioned and supported by NHS Bristol and Bristol City Council, which used Bristol as a test case ‘AnyCity’, and took a detailed look at our food scene, from its creation, production and disposal.

The report triggered a seismic change in how Bristol saw itself as a food city. It was really the beginning of the journey that now sees Bristol as a major food destination, and led to us to become the first Silver Sustainable Food City in 2016. We’re now well on our way with our bid for gold.

It looked at supply chains, city council procurement, restaurants, shops and waste management. It asked questions about what food security would look like if you excluded supermarkets. It considered the role of local food markets and abattoirs (many of which were closing). It asked what would happen if local heritage varieties, in fact variety in general, became extinct. If our local food markets were under threat, what would happen to the wisdom of local growers, with their understanding of their very particular patch of countryside.

Bristol Fruit Market

Our wholesale fruit (and vegetable) market in St Philips services an area from Pembrokeshire to Portsmouth, and Penzance to Oxford because of the closure of other regional wholesale markets.

So imagine a world where the Bristol Fruit market doesn’t exist. Without it, growers in Penzance would have to travel to Birmingham (270 miles away) or Heathrow (290 miles away).

The problematic role of supermarkets: how do they work, even when they sell ‘local’ food?

Supermarkets, who make up 96.4% of food retail, have ‘just in time’ ordering and delivery systems, and are these days completely separate from the city-wide food markets and the other local supply chains. Consider also that we currently import about half of our food in the UK – that’s 30% more than we did 40 years ago [1].

Even if your local supermarket sells local food, it will have travelled to and from distribution and packaging centres, and may even be more expensive than the same product that has been imported.

What about seasonality? Weather events such as the Beast from the East demonstrate how volatile a system of ‘putting all your eggs in one basket’ (or one supply chain) can be. Remember courgette-gate in 2017 [2]? A more pertinent question is why we expect cheap courgettes in January anyway. Over the last 40 years, supermarkets have successfully given us what we will buy, regardless of where in the world it comes from and what the impact of importing it will be.

Supermarkets have also greatly influenced the range of food sold. The ability to withstand transportation and refrigeration are often bigger factors than taste, provenance and variety. Diversity and seasonality have a place to flourish in regional food markets but local and heritage varieties don’t fit into the more homogenised world of big retail. Though I can’t find the source, I was told some years ago that a savoy cabbage can be as much as nine months old by the time it’s out on the shop floor for sale. Savoy cabbages keep very well …

Operating at scale

There’s a slaughterhouse near Merthyr Tydfil in Wales [3], the main abattoir supplying Tesco, which is open 24 hours a day seven days a week. Its capacity means that in order to be cost effective (which means processing 2,400 cattle and 24,000 lambs a week) it has to draw in livestock from all over the country, not just Wales. Even though it feels a bit like the tail wagging the dog, you have to admit it ticks that efficiency box …

How much of our food is bought from supermarkets?

For every pound spent in the UK, 39p is spent in food shops [4]

96.4% of this food is bought in supermarkets (as of Sept 2019), nearly a third from Tesco alone (the other two thirds are split between the other six) [5]

Only 1.7% of food is bought from an independent retailer. [5]

Definition 2: The environment – how and why are independent retailers part of the solution to climate change?

Definition 2: The environment – how and why are independent retailers part of the solution to climate change?

As well as a secure and reliable food system, we also need to make sure it doesn’t negatively impact the environment. This is where Better Food, Good Sixty, Wild Oats, Harvest, Scoopaway, Zero Green, The Community Farm and all the other independent retailers around Bristol come in. To misquote Shakespeare, ‘Though we be but little, we is fierce …’

As mentioned previously, independent food stores currently make up a tiny 1.7% of the food retail market in the UK. But we exist outside, or at least on the edge, of the cut and thrust of large-scale retailing. Within the bounds of remaining in existence, we can and do set our own agendas. We can commit to paying and playing fair. We can influence the way our local food suppliers grow, in our case towards organic certification – we did this recently with The Bristol Loaf (pictured left), a fantastic bread supplier who were on their way to organic, but needed an incentive to get Soil Association certification. The chance to be available in our three stores provided that incentive, and in the last 6 months, we’ve sold over 11,000 of their loaves.

We’re good for the local economy. Research shows that £10 spent with a local independent shop results in up to an additional £50 back into the local economy. People who live and work in a thriving independent scene will spend at local shops, who employ local people, who put that money back into the local community, and so the money circulates [6].

We’re also buying from and supporting sustainable local agriculture – farmers and growers who practice sound stewardship of our local environment. Adeys Farm in Berkeley, Gloucestershire are a great example of this. They supply most of our pork and beef products. We’ve worked with them for over 20 years. We visit them regularly; their standard of animal husbandry is exemplary. Read about them here.

We’re also buying from and supporting sustainable local agriculture – farmers and growers who practice sound stewardship of our local environment. Adeys Farm in Berkeley, Gloucestershire are a great example of this. They supply most of our pork and beef products. We’ve worked with them for over 20 years. We visit them regularly; their standard of animal husbandry is exemplary. Read about them here.

Joe Pardoe from Priors Grove (pictured, right) in Herefordshire, supply our orchard fruit every year. They’re among a dwindling band of orchards in the UK – a shocking 90% down since the 1950s [7]. We cherish them. They’re heroes.

We can encourage these suppliers to innovate, grow and take calculated risks, by offering them a secure and assured route to market, broadening out range, and offering consistency to shoppers.

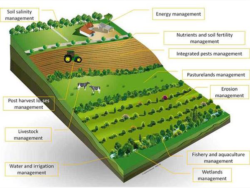

The thing all these have in common – meaning we’re not damaging or negatively impacting the environment – is that they’re organic! This matters because organic farming is a good environment for wildlife and biodiversity. It promotes healthier soils, which help combat climate change and prevent flooding and drought. It uses fewer pesticides and no artificial fertilisers or herbicides and bans the use of GM crops. And that’s just for starters. The Soil Association’s website explains it in much more detail.

The beautiful thing about the organic farming system is the integration and rotation of crops, livestock, fallow time etc, which work with the very best of nature with local wisdom and understanding. At its best, I think of it as the most brilliantly written poem – nothing is there unless it has a reason to be. It’s a whole, made up of crucial and integral parts. And the whole looks after the soil in a way conventional farmers are just waking up to, after years of relying on agricultural inputs – oil based fertilisers – and discovering their topsoil is, to put it mildly, in a very poor state. Organic farms have good fertile pasture land, and more trees and hedgerows that are also good carbon sequesters [8].

The beautiful thing about the organic farming system is the integration and rotation of crops, livestock, fallow time etc, which work with the very best of nature with local wisdom and understanding. At its best, I think of it as the most brilliantly written poem – nothing is there unless it has a reason to be. It’s a whole, made up of crucial and integral parts. And the whole looks after the soil in a way conventional farmers are just waking up to, after years of relying on agricultural inputs – oil based fertilisers – and discovering their topsoil is, to put it mildly, in a very poor state. Organic farms have good fertile pasture land, and more trees and hedgerows that are also good carbon sequesters [8].

What does the diet of future look like?

The Eat-Lancet report, published in January 2019 [9], tasked more than 30 world-leading scientists from across the globe to reach a scientific consensus that defines a healthy and sustainable diet.

It sparked many column inches about the best way to eat for a sustainable future.

These are the top takeaways of everything I’ve learnt:

- We definitely need to eat less meat and dairy, but we also need to be wary of eating and drinking too many products and processed foods containing environmentally complicated ingredients like soy, palm oil, cashew and coconut. They tend to put a burden on relatively new products, often from developing countries, often affected at the sharp end of climate change.

2. We definitely need to stop buying everything wrapped in plastic. Everyone has their own favourite shocking plastic fact. Mine currently is that a million plastic bottles are sold around the world every minute. But beware of bio-plastic. Read this excellent blog on City to Sea’s website for more information. If you can, the best thing to do is arm yourself with as much reusable packaging as you can and avoid it altogether (see @Refill for more).

3. We need to also see our diets in the context of what we know about eating locally.

3. We need to also see our diets in the context of what we know about eating locally.

Eating ‘local’ in the UK maybe should include meat. Speaking on Radio 4’s Today programme on 21st August, Patrick Holden (pictured, right) from the Sustainable Food Trust argues that as two thirds of the UK is pasture, (ideal for cows and sheep), we should be eating meat and dairy, but only from fully pasture-based systems, which can also store carbon. Just stop eating animals fed on grain – notably pork and poultry.

He says ‘We should align our future diets to the productive capacity of the nation where we live and in the UK that will mean a significant proportion of our diet coming from red meat from grass-fed systems’.

Conclusion and sources

Finally, I’d like to leave you with the thought that shopping is a form of direct action.

Joel Salatin, farmer, environmentalist and author, says ‘You, as a food buyer, have the distinct privilege of proactively participating in shaping the world your children will inherit’.

Independent retailers like Better Food give us access to food as it should be. Not necessarily the cheapest, but I would also contend that supermarkets have made us believe food is cheap. It isn’t. Somewhere down the line, someone’s paid the price.

References and useful links

[1] BBC News – Why the UK has such cheap food, Ratula Chakraborty & Paul Dobson, University of East Anglia 1/10/18

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-45559594

[2] Courgette prices rocket fourfold as cold snap leaves continental suppliers with zucchini shortage, This is Money, 17 January 2017

https://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-4127736/UK-supermarkets-grips-courgette-shortage.html

[3] Sustainable Food Trust: A good life and a good death (ref p8)

http://sustainablefoodtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Re-localising-farm-animal-slaughter.pdf

2 Sisters plans million pound investment in Merthyr

https://meatmanagement.com/2-sisters-plans-million-pound-investment-in-merthyr/

[4] House of Commons briefing paper: Retail sector in the UK, 29 October 2018 (ref Summary, p3)

http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06186/SN06186.pdf

[5] Market research from Kantar, Great Britain: Grocery Market Share (12 weeks ending 8/9/19)

https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/en/grocery-market-share/great-britain/snapshot/08.09.19/

[6] Fifteen reasons why you should shop at a local company, Small Business, 25 January 2018

https://smallbusiness.co.uk/fifteen-reasons-choose-local-company-2542429/

[7] Traditional orchard decline, People’s Trust for Endangered Species, 2019

https://ptes.org/campaigns/traditional-orchard-project/traditional-orchard-decline/

[8] Integrated farming image

https://www.pmfias.com/sustainable-agriculture-organic-farming-biofertilizers/

[9] Eat-Lancet Report, January 2019

https://eatforum.org/content/uploads/2019/01/EAT-Lancet_Commission_Summary_Report.pdf

Other useful links

Food miles

https://www.eta.co.uk/environmental-info/food-miles/

Local sustainability

https://www.naturalproductsglobal.com/europe/eat-more-red-meat-to-help-fight-against-climate-change-sft-boss-urges/

Plastic pollution

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jul/19/plastic-pollution-risks-near-permanent-contamination-of-natural-environment